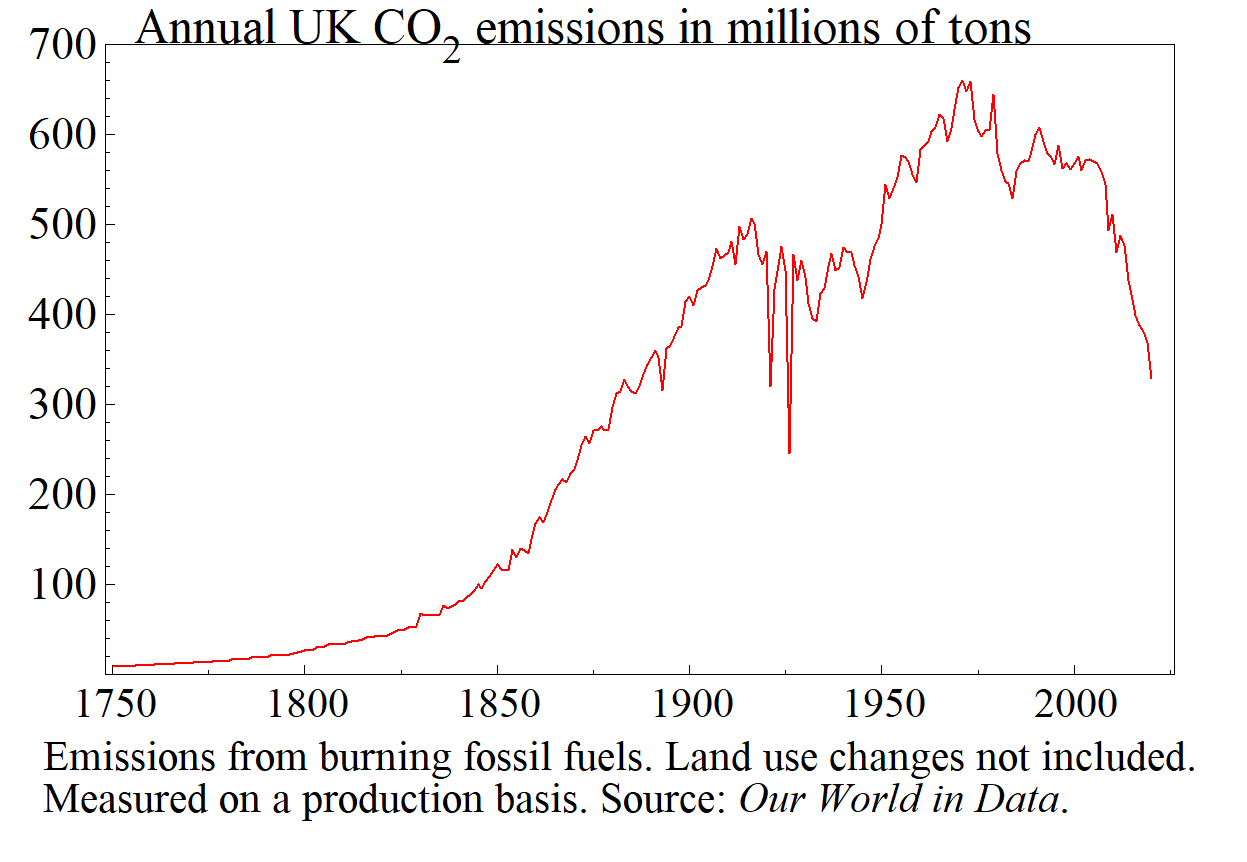

COP26 has come to an end and while its successes and failures are debated, the pressing question is “What now?” With so much at stake and the hope of limiting global temperatures to 1.5°C becoming increasingly more faint, it is now time for the UK government to stop talking and start doing.

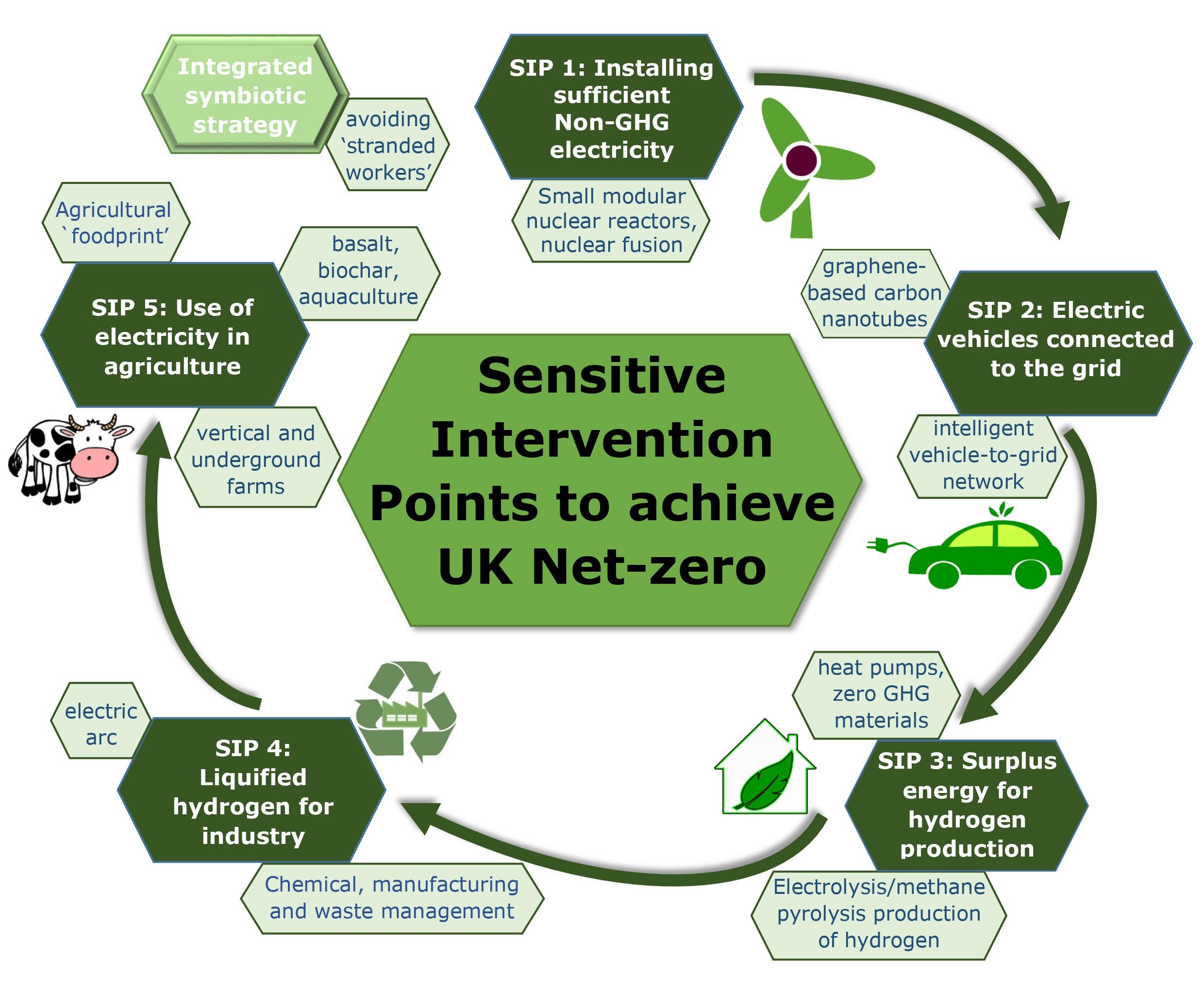

To reach its net zero target, there needs to be a widespread strategy that shifts all sectors away from their reliance on fossil fuels. This can be done. History shows us that many societal changes have sensitive intervention points (SIPs) – small changes that lead to larger shifts at great speed. For example, the shift to machine production sparked the Industrial Revolution. In order for the UK to change its future, SIPs in the post carbon transition could be the key.

In their new paper “Can the UK achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050?” Jennifer Castle and David Hendry propose five interacting sensitive intervention points that can move the UK toward a net-zero future.

1. Installing sufficient non-greenhouse gas electricity

2020 was a record year for UK renewable energy production, but there is still a long way to go to achieve a 100% target by 2035. The good news is the cost of renewable energy sources has plummeted in the past decade – a whopping 89% for solar and 70% for onshore wind. Moreover, wind energy costs for both on and offshore are anticipated to continue to fall by an additional 37-40% by 2050.

For those times when solar and wind do not generate enough power, research and development of small modular nuclear reactors as well as nuclear fusion methods could help to speed up the move to net zero.

2. Electric vehicles connected to the grid

By 2030 no new diesel or petrol run vehicle will be sold in the UK. Increasing the number of EVs in use will greatly increase electricity needs, but renewables generation is highly variable. A solution is vehicle-to-grid technology (V2G).

The average car is parked for 23 hours a day. This makes EVs ideal for acting as short-term storage units, providing unused power back to the grid while reimbursing owners for their surplus energy – thus encouraging uptake.

Additional benefits would come from technological improvements to EVs. Graphene-based carbon nanotubes can be built into the vehicle’s body, acting as an electrode supercapacitor and making the car the battery, improving driving range and cutting charging times.

3. Energy for hydrogen production

Hydrogen as an energy source is one that has great potential to replace natural gas in areas such as heating and cooking. Combined with an increased installation of ground and air source heat pumps, following major improvements in insulation, it could eliminate the 30% emissions currently emitted by housing.

It does take a lot of energy to produce hydrogen so using non-greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting methods as well as off-peak electricity, is vital to make it worthwhile. Electrolysis (using electricity to break water down into hydrogen and oxygen gas) and methane pyrolysis (the splitting of biomethane into hydrogen and carbon) would be effective means of production without emitting greenhouse gasses. The technology already exists. A gradual upscaling could see a complete shift in domestic use over the next 30 years given sufficient non-GHG electricity.

4. Producing and storing liquefied hydrogen

Hydrogen’s potential is not limited to replacing natural gas. Producing and storing it in liquefied form could make it available for use in carbon-intensive industries, like iron and steel manufacturing, owing to its high-heat capacity.

Other industries can also benefit from its use, as in fuel cells for heavy goods vehicles and buses. London Transport has announced its intention to use hydrogen-run vehicles within its fleet.

Of course electricity is needed to produce liquid hydrogen and appropriate storage would need to be constructed, but this is possible. Large-scale liquid hydrogen plants operated by NASA already exist in the United States.

5. Changes in agriculture

Lowering emissions in agriculture is one of the most difficult to achieve, but there are areas that can be greatly improved.

Behavioural changes are important, but there are also simple solutions such as the introduction of dietary additives that reduce methane production in ruminants. Additionally, using ground basalt as a fertilizer could also be a source of carbon capture, while reducing the use of nitrous oxide emitting nitrogen fertilisers.

A shift to vertical or underground farming can produce greater yields while using low-energy lighting and more efficient use of water. While electricity is needed, renewable sources can be used.

These five integrated sensitive intervention points can help usher in a net zero future for the UK. The already dramatic decline in the cost of renewable electricity has made it all the more possible to scale up production and begin to utilise emission free electricity and make gains in other fields such as transport, hydrogen production, industry, and agriculture.

There does not have to be a choice between economic growth and a green future. The move to net zero will bring new employment opportunities that could help to mitigate the impact felt by those who may lose out in the transition.

Not only is it possible for the UK to achieve net zero, it makes economic sense.

Angela Wenham, Project Manager, Climate Econometrics

Angela Wenham, Project Manager, Climate Econometrics

David Hendry, Co-Director, Climate Econometrics

David Hendry, Co-Director, Climate Econometrics

Jennifer Castle, Associate, Climate Econometrics

Jennifer Castle, Associate, Climate Econometrics

Banner photo by Nicholas Doherty on Unsplash